Self-strengthening the Kawawana territory of life

The evolution of this guidance began more than a decade ago: the custodians of the Kawawana territory of life in Senegal were facing major threats to both their territory and community livelihoods. They understood that to address these threats, their ‘territory of life’ was central and needed to be restored. For that, also their traditional rules for access and use of natural resources, integrated with new understandings and tools, needed to be better recognized and respected. This is exactly what they achieved! How did they do it? They engaged in a process of reflection, discussion, and action: a ‘self-strengthening process’.

The custodians of the Kawawana territory of life began their self-strengthening process in late 2008, Their story illustrates the power of such a process and provides an example of how it can be approached.

The self-strengthening process started in late 2008, when the term Kawawana did not yet exist and the local estuarine territory was in a truly bad shape. At an initial meeting among leaders of the Mangagoulack rural municipality, representatives of the local fisher’s organization, and visitors from the ICCA Consortium, the difficult circumstances were discussed. They agreed that their territory needed to be restored to bring decent livelihoods back to the community. In their view, this could be done only if the community was able to reinstate its traditional rules for access and use of natural resources. The traditional rules would put an end to the pillage of the natural resources that was happening under their eyes, by anyone able to fish, cut, gather or collect anything in their territory. For that, however, the backing and support of the government was necessary… They all knew that a leader of a neighbouring community was sent to jail for having unilaterally attempted to enforce local fishing rules. They were scared by that, and saw no way out of the quandary.

With a strong mandate from all participants in the initial meeting, the ICCA Consortium visitors were able to quickly obtain resources to support the community self-strengthening process. Early in 2009, they began with a three-week set of intensive meetings among 150 representatives from the eight villages that comprise the community. The meetings developed as relatively informal but highly focused grassroots discussions, with people examining their situation, envisioning what they wished to achieve and planning what to do. The process was supported by a team of three external advisers, comprising a fishery biologist, an agro-economist and a governance expert and overall process facilitator.

At the beginning, a group of more than twenty experienced and respected fishermen from the eight villages got together to analyze the present and historical situation of the local fisheries, and identified and described trends in the diversity and size of their catch. Then a much broader group of village representatives joined in and heard from the fishermen. Together, they recalled the history of their community, their deep, multiple cultural and spiritual connections with their territory (the Djola culture is as complex and rich as one can imagine) and their shared current ecological and socio-economic situation. The larger group was then accompanied to identify their desired future, or what they mean when they said they want a “good life” (Bourong Badiaké). It turned out that what they all meant was peace, community solidarity, prosperity, a better diet for all, a stop to the urban exodus, and a healthy and productive local environment. For all of this, they recognized that their territory of life– which they named Kawawana or “our collective natural heritage to be conserved by us all”– was essential. Through further discussions and analyses, they all agreed that they needed to restore their Kawawana via the recognition and respect of their traditional rules (integrated with modern tools for biological monitoring). Ultimately, they believed that this was the single most important factor to bring about all the good life results they wished to achieve. This realization was a very powerful moment for all those involved.

For all of this, they recognized that their territory of life– which they named Kawawana or “our collective natural heritage to be conserved by us all”– was essential.

.

While these discussions were taking place, the initial fishermen group was also receiving training on biological monitoring and another group called Kaninguloor was created to discuss what indicators would reveal the desired change towards the “good life” (Bourong Badiaké) and how those indicators could be assessed. Two dedicated teams (a fishery monitoring group and the Kaninguloor group) agreed to keep measuring and assessing their sets of chosen indicators, tracking whether they were going to approach the desired/ expected change, if and when their traditional rules were to be reinstated.

.

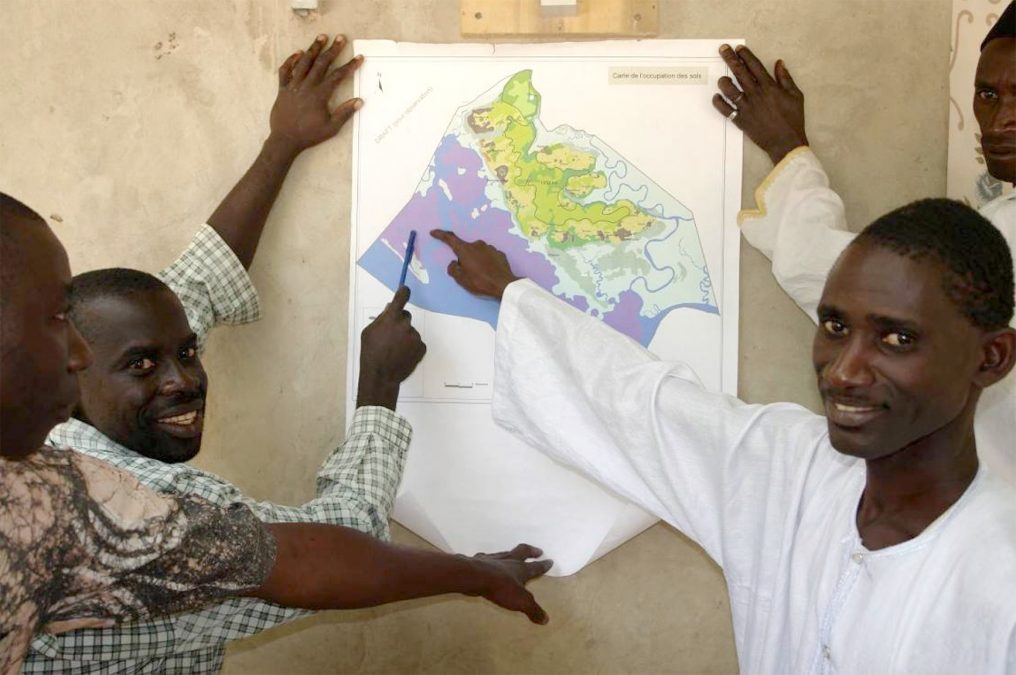

Then the representatives planned together what they needed to do. Most fundamentally, they needed formal recognition and respect for their local knowledge and rules in the access and use of natural resources. For that, they decided to establish Kawawana as their ’community conserved area’ and strive to get it formally recognized. Information received from the ICCA Consortium had made the community aware of some national and international legal and policy bases on which their conserved area could be recognized. These included Senegal’s Law of Decentralization, as well as the country’s status as a Party to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which recommends supporting community-based conservation. This information was crucial, and it empowered the community with the confidence it needed to act. The 150 representatives took advantage of their time together to develop and agree upon a management plan for their community conserved area (including different zones, rules, signage, surveillance, and penalties for infraction); a governance structure (with various roles for different institutions); a monitoring system for the governance and management results; a communication plan; and complementary initiatives to enhance livelihoods, support the activities of women, identify allies and partners at various levels and seek the formal recognition of the community conserved area.

In the eighteen months that followed, all that had been planned was actually implemented. The crucial factor was the tireless work of a few leaders who acted as community diplomats, with intelligence and determination and backed by strong community support. After formal recognition by the Mangagoulack rural municipality in 2009, the patient work of information sharing and advocacy continued for many months with the fishery and forestry departments and many others. Finally, however, in March and June 2010, Kawawana obtained formal recognition certificates from the Regional Council and the Governor of the Casamance Region. This was the fullest and most formal recognition they could have ever imagined obtaining! The community celebrated this result in earnest, starting with the wisest elder ladies setting up fetishes to signal the diverse zones and fishing rules. Then the men set up poles and panels to mark the same zones, with specific descriptions of the fishing rules. And, finally, everyone in the community who could do so attended the major event/celebration, where authorities and partners came to declare the formal entry into force of the Kawawana rules. It included speeches, food, music and general rejoicing.

Finally, however, in March and June 2010, Kawawana obtained formal recognition certificates from the Regional Council and the Governor of the Casamance Region. This was the fullest and most formal recognition they could have ever imagined obtaining!

While seeking official recognition, the community had also been seeking support to implement their management plan. When the management rules were formally adopted, they could be readily enforced with the help of a small boat and engine and complementary equipment provided with help from a local Foundation (FIBA). Surveillance of the respect of the rules was not always easy, and some conflict situations developed with non-local fishermen, but the Fishery Agency and Prefect backed the surveillance team and local diplomatic capacities did the rest. To strengthen their role, the volunteer fishermen on the surveillance team pulled resources together to buy themselves some training from the government fishery agency, after which they would be considered semi-formal agents. As the FIBA Foundation pursued conservation objectives, it asked the community to also set up a monitoring team for non-fish biodiversity, which was promptly done.

.

Less than three years after official recognition of the community conserved area, all monitoring teams were showing excellent results. The fisheries and local biodiversity showed impressive improvements (the original fish diversity reappeared, birds, dolphins and crocodiles went up in numbers and some fishermen said that their fish catch had quadrupled!). The indicators of overall wellbeing also improved, in particular regarding migration (fewer people migrated away and some returned to the villages) and the local diet (people were again eating the good fish they loved, which had nearly disappeared from their waters). The other indicators of Bourong Badiaké were also relatively good, but they had not been bad at the beginning and they proved less ‘sensitive’ than others to any type of change.

In the years that followed, the main governing body of Kawawana kept meeting to deal with various issues, and continued to function on its own, with no project support. There was an attempt to raise funds for Kawawana through a small bicycle renting business, but the business proved too complex and time consuming for the local volunteers. Remarkably, the fishermen active in the surveillance of the community conserved area have continued doing their job, year after year, on a voluntary basis. The community conserved area was even voluntarily expanded in size. But it is clear that governing and managing a community conserved area on a purely voluntary basis is demanding important sacrifices from people who have no time or resources to spare. For example, the Kawawana surveillance team is currently facing a problem because the engine of their surveillance boat and an important part of the monitoring and surveillance equipment have been damaged in an accident caused by bad weather. Local people are active seeking resources to reconstitute their means. No one can say how long their volunteer efforts will remain viable.

The small amounts of external funding sporadically received from the ICCA Consortium has been for targeted initiatives, such as a radio programme in local language, which has made Kawawana locally well-known and respected. Recognition has not only been local. Kawawana has received two international awards for its accomplishments and inspired other communities to become custodians of their own conserved areas in Senegal.

Together, and with the help of another GEF SGP grant, the community custodians of territories of life in Senegal have developed a national network. At the time of this writing, in 2020, the national network is advocating for national policies to formally back community conserved areas and enhance their security. However, the advocacy work is still not strong, and legal advice is needed.

Throughout the twelve-year process briefly described above, the Kawawana custodian community has been self-strengthening its territory of life. If the beginning was very intense, the continuation has been steady. The community began strengthening itself by reflecting on its situation, analyzing it, documenting it, informing itself, agreeing on a course of action, planning and committing together, weaving relations with allies and partners, doing careful diplomatic work, being accepted, recognized and supported and celebrating its achievements. It then continued strengthening by working together for years, governing and managing their territory, getting trained in new skills, communicating about their territory of life , learning lessons, sharing these lessons with other custodian communities and seeking ways to improve the overall policy context in Senegal. Some external facilitation and support at crucial times have been important, but the bulk of contributions and efforts have been provided locally. Today, the Kawawana custodian community has not solved all its problems and has its ups and downs, like all communities… but it is much stronger than ten years ago, and its territory of life is healthy and alive!

Photos © Grazia Borrini-Feyerabend